Notes from a 15-minute talk given by Fay Ballard to artist members of the Drawing Room’s Professional Network, London, in September 2014.

I’m going to begin by describing some recent drawing and then go on to look at the research which underpins it.

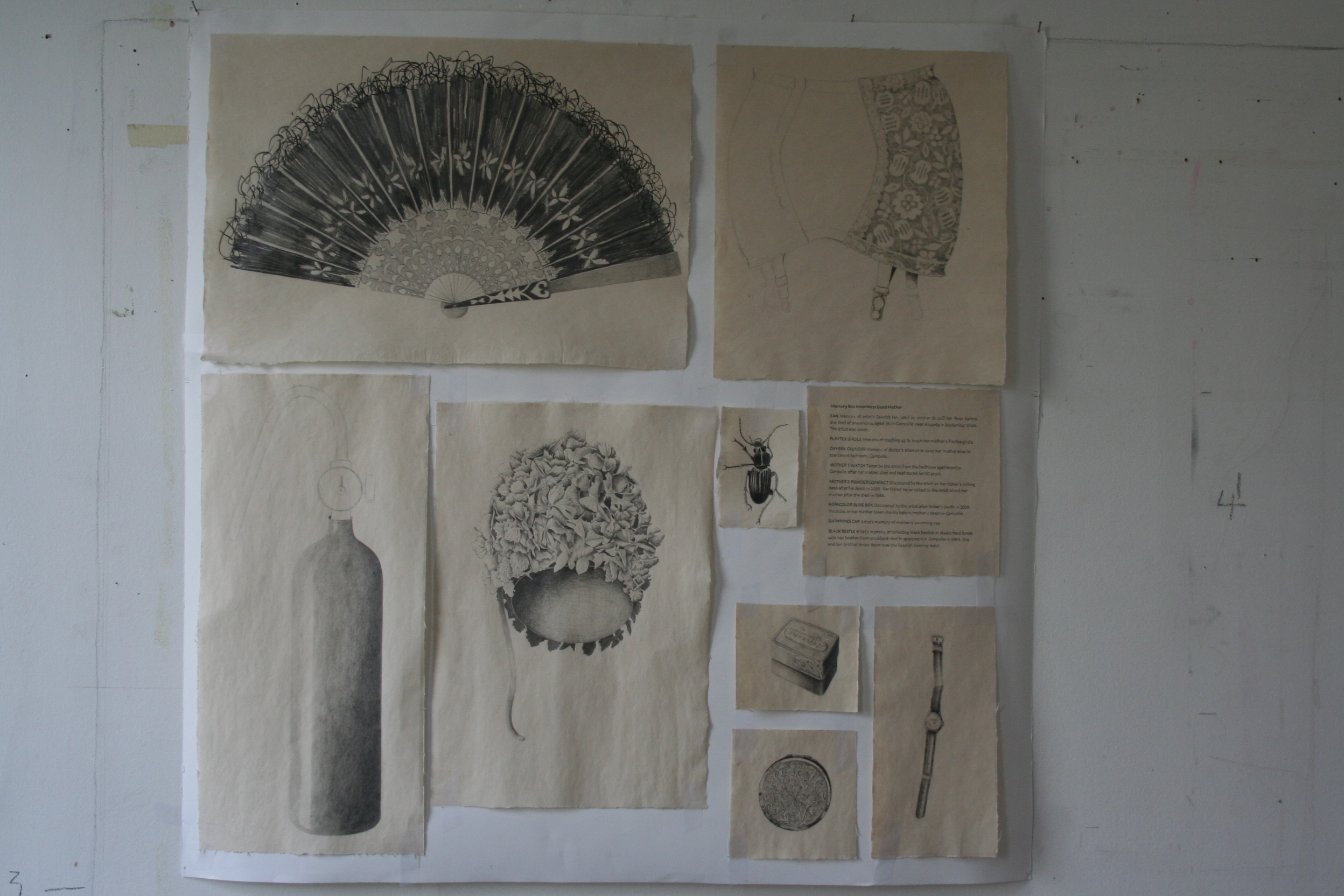

I’ve been working on a series of Memory Boxes which explore my childhood memories. Each Box contains a number of individual drawings. I’ve selected objects from my life and drawn them either from direct observation or from memory. The first three were made between 2010 and 2012 and are called ‘Drawn from Life’, ‘Drawn from Memory’ and ‘About My Father’. I have just completed a forth, ‘Memory Box: Dead Mother’.

Each Box is accompanied by an inventory – a list describing each object briefly – in the style of a local house clearance sale. This reminds me of the time when I accompanied my parents to a local house auction to buy some furniture and returning with a small pink chair. For ‘Memory Box: Dead Mother’, however, I hand wrote the text and incorporated it into the picture.

I’m telling a story which centres on my mother who died suddenly on holiday in Spain in 1964 when I was seven. My father never discussed my mother with me after her death; she wasn’t mentioned amongst my siblings. There were no photos of her at home.

I took her watch from the room where she died and kept it hidden. It was only after the death of my father, the novelist, J G Ballard, in 2009, that I felt able to think freely and speak openly about her.

As I began to clear my father’s home, the place where I grew up, I came across photos of my mother and some of her things which my father had kept hidden –her powder compact, a box of agfacolor slides of her on holiday when she died, and a group of small black and white photos of her playing with me and my brother on the sands at Prestatyn in North Wales. For the first time I was able to study her face, her body, her clothes and her shoes. Did I have the same eyebrows and nose?

Through drawing, I began to give ‘voice’ to my mother -to make her explicit. I drew her watch and powder compact and I made pencil studies of her face, body, clothes, bag and shoes to help bring her back and make her concrete.

Then I began a process of drawing other objects which held personal significance which I’d found when clearing the family home.

I then made a second series of individual drawings, drawing objects from memory, followed by a third set of drawings of objects which represented my father. I’ve just completed a forth, ‘Memory Box: Dead Mother’. The drawings from memory are fragmented, improvised, out of scale, and at times false. I recall folding an origami elephant with my father, and made a drawing, but when I found the origami book afterwards, there was no elephant exercise. Had I imagined the memory or perhaps we didn’t use the book on that occasion?

So what are the ideas associated with these Boxes?

In her book ‘Evocative Objects’, Sherry Turkle, a psychologist at MIT, says: ‘We find it familiar to consider objects as useful or aesthetic, as necessities or vain indulgences. We are on less familiar ground when we consider objects as companions to our emotional lives or as provocations to thought. She refers to Claude Levi-Strauss, who described bricolage as a way of combining and re-combining a closed set of materials to come up with new ideas. Material things, for Levi-Strauss, were goods-to-think-with. Turkle’s book makes the case for the object as a companion in life experience.

Daniel Miller, an anthropologist working at UCL, goes further in his book ‘Stuff’ when he claims that objects not only represent us but also create us. He says: ‘Our houses, with our stuff are our autobiographies. In homes, people create themselves through stuff’. He quotes Hegel: ‘We are able to see ourselves in this extension of ourselves. We can come to understand who we are.’

Miller believes that moving house becomes a means to reshuffle relationships and memories by bringing them back into consciousness, by making them explicit and for deciding which ones to reinforce, which ones to abandon or put on hold. The paring down of objects transforms the memory from a more actual to a more idealised one.

The importance of an object as an emotional companion can be traced back to the toddler’s ‘transitional object’ as defined by the psychologist, Donald Winnicott. At around two and a half years old, the child begins to act out the child/mother relationship where its state of mind is partly me/partly not me. It does this through play-acting by choosing an object, such as a teddy bear and acting out small dramas with this object. So it might say ‘good teddy, have some more food’, or ‘bad teddy, time for your sleep’. The object becomes smelly and dirty, and its familiarity becomes a comfort to the child. It can’t be washed because that would change, in fact, destroy, the object. It would become alien.

And what of the photographs I found of my mother, these small black and white portraits, photos of her playing with me and my brother, and others showing her sitting with her family? These are my evidence that she existed in my life. In ‘Camera Lucida’, Roland Barthes questions the relationship between photographs and memory by suggesting that photos are the memory, can take the place of memory, or recreate ideas of the past through the present.

For each Memory Box, I have arranged my drawings inside shallow vitrines; containers where memories are ordered, edited, categorized, kept under wraps and preserved, hinting at the museum display or an archaeological find, reinforced by the inventory caption displayed alongside.

The psychologists, Martin Conway, Lucy Justice and Catriona Morrison outline the modern view of memory in ‘The Psychologist’ (July 2014). Memories are mental constructions. They represent only short time slices of experience, they are ‘time-compressed’, and because of this they will never fully represent an experience, rather the fragments derived from experience that they contain are more a ’sample’ of experience than a full or literal record. In this respect then memories are psychological representations and not like photographs, videos or other types of recording. Because of their constructed nature, memories are prone to error, distortion, confabulation, and even wholly false memories may at times arise.

Kathy Kubicki, curator and writer, in her essay on my exhibition ‘House Clearance’, references the French feminist philosopher and psychoanalyst, Julia Kristeva. Kristeva writes on the importance of pre-verbal language between mother and baby at the pre-Oedipal phase, when the bodies of mother and child are in contact. Kristeva imagines the patterns or play of forces present in language before the baby can use language – the ‘pulsations’ ‘pauses’ and ‘rhythms’ as well as silence and absence . Kubicki notes that creatively, this space as described by Kristeva, is fluid and multiform, a kind of pleasurable creative excess over precise meaning.

Kristeva’s ideas may be connected to the work of Sally Jakobi, a Jungian psychologist I heard speak at the Centre for Analytical Psychology. She made electronically monitored recordings of 14 under 24-hour old babies’ sucking rates and their mother’ simultaneous heart rates at a London maternity hospital some 30 years ago. These recordings show that the mother’s heart rate frequently synchronises with the rhythm of her baby’s sucks or alternatively that her baby appears to suck in time with the beat of the mother’s heart. Thus, the human need to reach out and connect may start in the uterus. Perhaps I’m searching and connecting with my mother through the repetitive, rhythmic, mark-making of drawing?

Melanie Klein’s psychoanalytic work focuses on the important relationship between mother and child, and for me, this relationship has become uppermost in my practice. In Klein’s work, the baby begins its development in the paranoid schizoid position, by viewing the mother as either good or bad depending upon the baby’s frustration with her when it is hungry, thirsty and so on. This psychic position is replaced by the repressive stage when the baby shows concern for the mother and develops the desire to preserve the mother from its aggression and destructive instincts. Restorative fantasies form part of this stage to resolve earlier depressive anxiety and this is named reparation which is viewed as a genuine expression of love for the mother.

This process of reparation has since been emphasised in writing on art and creativity as it manifests by means of creative labour on the part of the individual, most notably discussed by Hanna Segal and Adrian Stokes. For me, this means trying to reconstruct my absent mother through the act of drawing.

When my father was alive, I drew plants mostly and these often displayed an uncanny quality. The uncanny, Freud said, signalled the return of the repressed, which was one possible outcome of such denial.

September 2014