– William Viney, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Centre for Medical Humanities and Department of English Studies, Durham University.

On the 19th October we staged a collaborative event with the Memory Network, Hearing the Voice, and the Durham Book Festival. The intention was to discuss the intensely interesting but rather murky relationship between our memories, the phenomena of ‘auditory-verbal hallucination’, and associated acts of literary creation. As Memory Network’s co-investigator Pat Waugh has observed, there seems a rich seam connecting unusual memories, literary experiment, and dissociated experiences. With this seam identified but rarely discussed in public, we thought it a good idea to gather together a team of writers, literary and cultural theorists, psychologists, and those who have an expertise forged through experiencing voices where no external stimulus is present, to unpack the relationship between voices, memory, and forgetting.

Angela Woods (co-director of Hearing the Voice) chaired an extraordinary panel composed of Professor Lisa Blackman (Goldsmiths College, London), Professor Richard Bentall (University of Bangor), and leading-figure in the voice-hearing movement, Eleanor Longden (Intervoice). Each reflected on their own experiences, as clinicians, researchers, practitioners, observers, and those who had direct experience of voice-hearing, with regard to the difficulty of reconciling a single, narrated memory that is capable of healing the stigma and alienation attached to a psychiatric diagnosis. Instead, Blackman, Bentall, and Longden explained how a range of narrative-based and dialogical techniques are used to manage memories that are both oppressively attached and bewilderingly detached from our lived present.

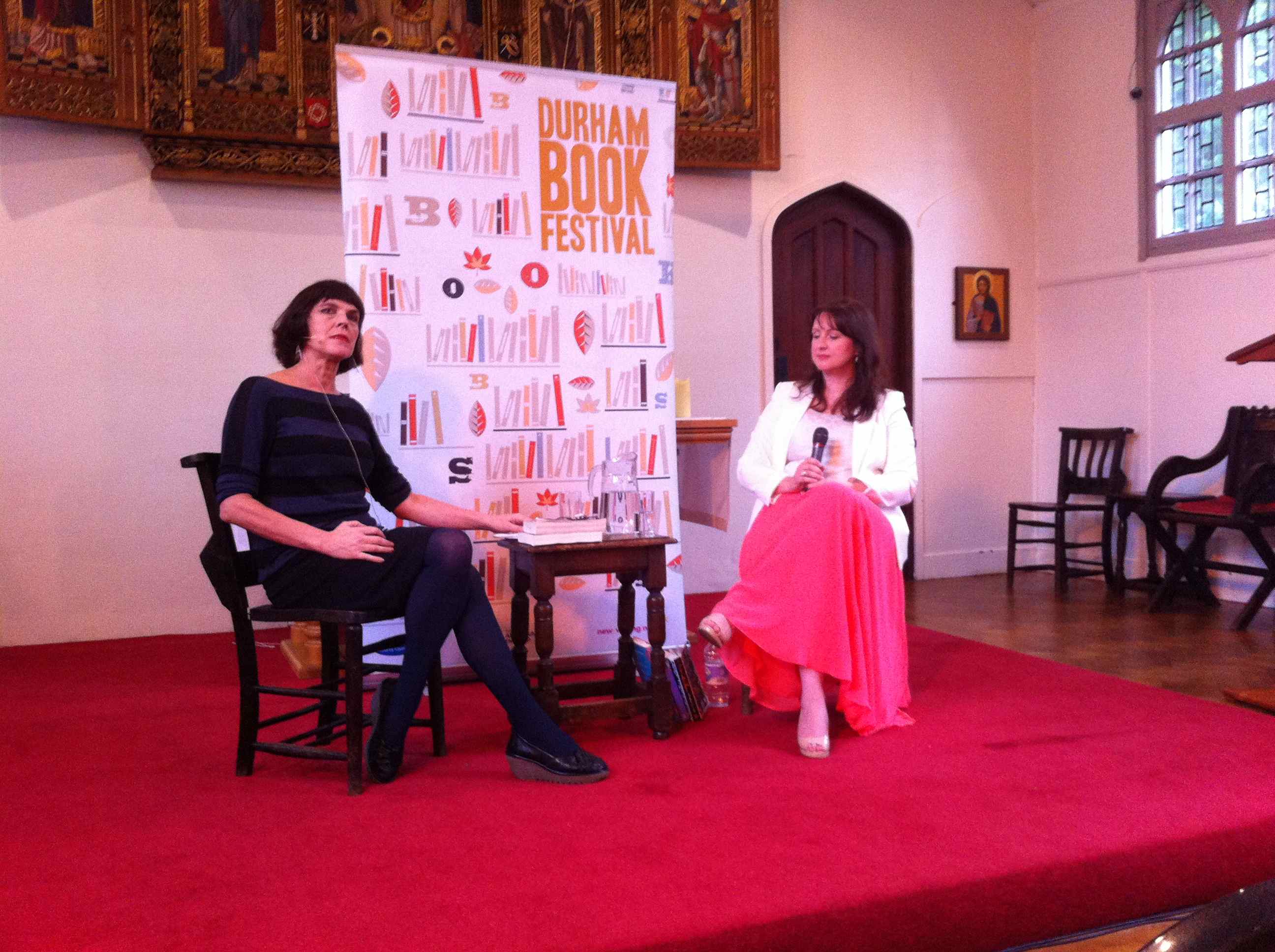

The next session began with a reading from the award-winning author Carolyn Jess-Cooke. Discussing her novel, The Boy Who Could See Demons, with Pat Waugh, this session analysed how best to imagine and remember episodes of psychosis. Jess-Cooke’s novel represents, among other things, a careful exploration of how clinicians must draw upon their memories in when working with their patients. The clinician in her novel must reconcile the memory of her daughter’s own psychotic episodes as they are triggered are through her care for the boy who sees demons, leading to a complex and compelling narrative experiment in focus, voice, and reconstruction. This conversation interrogated the imaginative content of memory, its presence in literary composition, and the uneven and uneasy relationship between the worlds of the mystic-psychotic and the worlds of those that care for them.

It’s clear that Will Storr’s experiences with the so-called ‘heretics’ of contemporary science put him in touch with some rather unusual and dangerous personalities. Among these included a holiday with Holocaust-denier David Irving and time spent with the influential climate sceptic Lord Monckton. Aside from entertaining us with tales of investigative daring-do, Storr’s great contribution to our event was to speak with Charles Fernyhough about the relationship between scientific fact and patient experience. Since both writers have tried to understand the sciences of mind in their prose, Storr and Fernyhough were able to reflect upon the difficulty of representing the dissent against scientific wisdom in fiction and nonfiction, the personal and political quality of transcribing the memories of others, and the relationship contemporary psychiatrists have taken towards patients whose stories do not conform to accepted diagnostic models. Some wider re all kinds of scepticism equally ‘healthy’? Should we give equal credence to the testimonies of so-called ‘heretics’ and ‘professionals’?

Our time spent together on 19th October revealed to me how frequently we think about human memory through the false dichotomy of norms and extremes. I hope that by challenging how we conceptualise the times, locations, and media of recollection, we were able to shed some light on how experience always exceeds those times, locations and media. And, if we only engage with extremes and their shadows, we risk rehearsing the extremism of biomedical and literary models of understanding, failing to see how experience is always more than the models available to us. If you’re interested in learning more about these debates, please visit this and the Hearing the Voice website, where video recordings will soon be available.